SPORTS CAR CENTRE PRESENTS

SPORTS CAR CENTRE PRESENTS

Motoring news from around the world - July 2019

The Legendary ‘Blower’ Bentley

As Bentley marks its centenary year in 2019, the British company’s ground-breaking supercharged model of the pre-war years won the marque a legion of motor sport fans around the world.

The legendary ‘Blower’ Bentley, with a supercharged engine, was sensationally quick in 1929. Especially with Bentley Boy, Sir Henry ‘Tim’ Birkin, sat behind the steering wheel.

Birkin and the Blower are intrinsically linked together in this sepia-toned era of British motor racing history. It was Birkin’s quest for speed that created the Blower, later recording heroic drives at the Le Mans 24 Hours and the French Grand Prix. He also broke the Brooklands outer-circuit lap record, the most coveted racing circuit of the time.

The supercharged engine ultimately ensured the 4 1/2 Litre model became the most iconic racing Bentley of the pre-war years. The Bentley 4 1/2 Litre was nearing the end of its development cycle by 1928, as other manufacturers finally began to catch up with founder W.O. Bentley’s superlative engine design. W.O.’s response was to increase the engine capacity, and his 6 1/2 Litre model won Le Mans in 1929 and 1930.

However, racing driver Sir Henry Birkin, who was already a schoolboy hero across Britain for his considerable achievements on the track, had another idea. He wanted to apply an innovative supercharger to the engine of the existing 4 1/2 Litre car instead.

To W.O.’s displeasure, Birkin persuaded Bentley’s new owner and chairman, fellow Bentley Boy and British financier, Woolf Barnato, to build him five supercharged Blowers for the racetrack. And to meet the racing rules of the era, 50 production Blower Bentleys were built for the road too.

Placing the supercharger in front of the crankshaft gave the Blower Bentley a unique appearance. It increased the power of the 4 1/2 Litre from 110 bhp to 175 bhp and, with Birkin at the wheel, it was sensationally fast.

W.O. Bentley described Birkin as “the greatest Briton of his time”. An aristocrat who fought in the First World War, Birkin returned from the front with a thirst for adrenaline and a total disregard for danger on the racetrack.

His dual with Mercedes-Benz driver, Rudolf Caracciola at the 1930 Le Mans 24 Hour has passed into legend. Bentley fielded three team Speed Sixes for the event, as well as Birkin’s team of supercharged 4 1/2 Litre Bentleys.

Birkin and Caracciola were neck and neck from the start, with the British hero at one point passing his rival at high-speed with two wheels on the grass. Neither car lasted the course and the race was eventually won by Barnato in a Bentley Speed Six.

Few cars have enjoyed the impact of the Blower Bentley. Many believe that Birkin only knew one way to drive, flat out for the win. Had he managed his race better over the gruelling 24-hour period at Le Mans, the result may have been different.

The Blower’s finest hour was in the 1930 French Grand Prix at Pau when, amid a field of lighter Bugattis, Birkin drove his two-ton car to a remarkable second place podium finish. The Blower is still believed to be the heaviest car ever entered in a Grand Prix.

Another version of the Blower was later converted into a single-seater and raced on the banked circuit at Brooklands in Surrey. With the engine output increased to 240 bhp, Birkin achieved 222 km/h (137.9 mph) when breaking the Brooklands lap record, his car often airborne due to the poor quality of the surface.

July 10, 2019 marks Bentley’s 100th year — a milestone achieved by only a few companies. To celebrate the occasion, a year-long series of special activities has been planned, with celebrations at events around the world. These will showcase Bentley’s motoring evolution over the last 100 years.

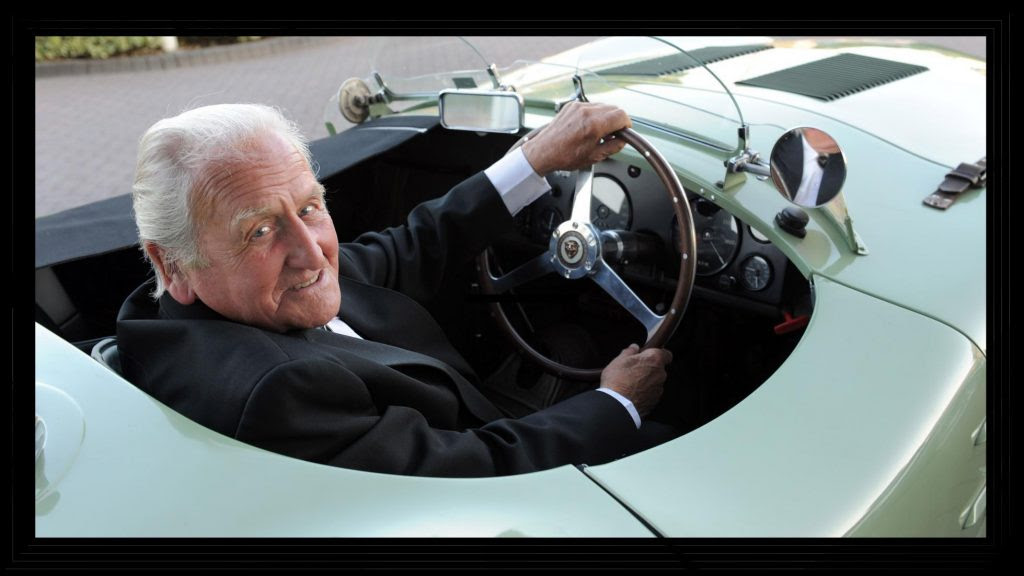

Norman Dewis, the legendary Jaguar test and racing driver, has passed away

Norman Dewis started working at the Humber factory when he was only 14 years old. After a stint at Armtrong Siddeley he joined the RAF during World War II, where he served as a gunner aboard a Blenheim bomber.

After the war he joined Jaguar, where one of his first projects was also one of his most consequential: he helped develop the first disc brakes.

Dewis was a very fast gentleman. In fact, for a while he was the world’s fastest, at least in a production car. In 1953 he set the record of 172.412 mph (277.470 kph) in a modified XK120, on a closed off section of the high-speed autoroute between Jabbeke and Aalter in Belgium.

In 1955, Dewis raced in the Le Mans 24 Hours, putting him amongst drivers like Moss, Mike Hawthorn, and Juan Manuel Fangio.

One of his most memorable feats was when he drove a brand new Jaguar E-Type 700 miles through Europe to its first unveiling at the Geneva Motor Show in 1961. Norman only stopped for fuel and spent 15 hours behind the wheel. Imagine doing that today – taking a brand new model, driving it with no camouflage, no backup, and no support vehicle all the way through Europe, then displaying it for the entire motoring press and the world the next day.

Another memorable, if more infamous feat, was when Norman survived a high speed crash at MIRA in the only existing Jaguar XJ13 race car in 1971. The crash wasn’t his fault, it was caused by a damaged tire. Luckily, Norman was unharmed.

We will all miss him. He was 98 years old.

John Wyer

The man behind those blue-and-orange Le Mans winners.

The Gulf Oil logo. Powder blue and tangerine orange. Low-slung Ford GT40s, mighty Porsche 917s, open-top Mirage-Fords. All are synonymous with John Wyer, the Englishman who spent American oil-industry dollars so effectively that he became known as the greatest team principal of his generation – but who might never have gained that reputation if he hadn’t been fired by Ford.

Wyer was the standard-setter in motor racing team management throughout the 1960s and early 1970s, the meticulous planner who could also think clearly and make smart decisions in the heat of battle. Wyer applied his natural fastidiousness to preparing for every eventuality, his engineer’s mind to suggesting improvements in car design, engines and components, and his access to unrivalled information to shape race strategies. That information came from his chief engineer, John Horsman, who recorded details at every race about his cars’ mechanical wear rates and fuel consumption.

Wyer was also known for his patrician air, razor-sharp one-liners, and ability to cut racing drivers down to size with the piercing stare which earned him the nickname ‘Death Ray’. He had, by his own admission, “an inability to suffer fools with any show of pleasure,” and during the early years of the GT40 programme this forthrightness sat uncomfortably with the corporate politics at Ford Motor Company.

Wyer was involved with the GT40 almost right from the start. This was largely because, purely by chance, he happened to visit Carroll Shelby’s workshops in Los Angeles on the same day in April 1963 as the Ford executive responsible for monitoring the corporation’s investment in Shelby-American Inc. Wyer wrote in his book, The Certain Sound: “It has been a source of astonishment to me that the really major landmarks in my life have so often seemed fortuitous at the time.”

Ford was impressed by the way Wyer had successfully formed a racing team for Aston Martin and directed the British marque to a 1-2 at Le Mans in 1959, when the race was won by the DBR1 of Roy Salvadori and Shelby. Wyer was less impressed with Ford’s employment offer. He had already decided “whatever I did next would be as far removed as possible from racing and sports cars,” but at a hastily arranged meeting in Detroit, Ford product manager Don Frey persuaded him to change his mind. For a while, Wyer and Ford looked like a working partnership made in heaven, but within a year or two each had formed different ideas about how the GT40 should be turned into a winner. And ideas were badly needed, because Ford’s first showings at Le Mans in 1964 and ’65 were dismal.

At Ford’s first attempt to win the French 24-hour race, all three GT40s failed to finish. At the second attempt, no fewer than six GT40s ran in the race, but still none lasted the distance. This was more than disappointing. This was humiliating. Ford had been spurned in its attempt to buyout Ferrari in 1963 and was hellbent on giving Enzo a slap in the face, but while all the Fords faltered in ’64 and ’65, Ferrari won both times.

After the ’65 race, some senior executives at Ford World Headquarters in Dearborn called for the GT40 programme to be axed. This foreign adventure had already cost more than $6 million and there was no point throwing more good money after bad. But others argued that fuelling a race programme with cubic dollars was only part of the solution, cubic inches were just as important and sadly lacking. A plan formed to forget the GT40’s iron-block 289cu in. (4.7-litre) V8 Cobra engine, forget also the aluminium Indianapolis-specification ‘260’ (4.3-litre) V8, and adopt the mighty ‘427’ (7-litre) unit from NASCAR racing. This, however, would require extensive revisions to the GT40’s chassis and systems.

Wyer disagreed with this proposal, advising that an easier route to success would be to continue developing the smaller-engined GT40 – but the men in Dearborn were no longer listening. Control of the GT40 programme was moved across the Atlantic to Shelby-American Inc., the team that might have got the gig in the first place. Ford’s settlement with Wyer entitled his business, J.W. Automotive Engineering, to provide parts and service for GT40s for three years and to produce more GT40s as required. There was a guaranteed profit of £1,000 per car, plus a $100,000 budget for Wyer to support private GT40 owners in international competition. A lucrative deal, but demotion.

This is when Texan oil man Grady Davis came riding into Wyer’s life like a knight in shining armour. Davis was a vice-president with Gulf Oil Corporation in Pittsburgh, but more than that, he was also a racing enthusiast who had run his own team in Sports Car Club of America (SCCA) events. Davis initially contacted Wyer because he wanted a street-legal(ish) GT40 for his personal use, but as the two men got talking it became clear they could benefit each other more significantly. Davis, who believed Gulf’s international brand-profile could be raised through sports car racing, saw in Wyer the man for the job. And Wyer, who believed Ford had been wrong to drop him, saw in Davis the financial resources to prove it.

And so it turned out. Oil dollars were pumped to Britain in sufficient quantity for Wyer to demonstrate that a smaller-engined GT40 could indeed win Le Mans. With 4.7- or 4.9-litre engines, JW Gulf GT40s won five of the eight International Championship for Makes rounds they contested in 1968, even though they were old warhorses up against Porsche’s newer 907 and 908. And at Le Mans it was the blue-and-orange GT40 of Pedro Rodriguez and Lucien Bianchi which crossed the line first.

The ’68 Le Mans-winning car, chassis 1075, returned to France in ’69, where it faced tougher opposition including two works Porsche 908 Coupés and three new 917s – and won again. In fact 1075 became the most successful of all GT40s, achieving five outright victories in 11 races over two seasons. Four of those victories were scored with Jacky Ickx in the driver pairing; two with Brian Redman, Lucien Bianchi, and Jackie Oliver; and one with Pedro Rodriguez. The remarkable story of those successes, of the GT40 more broadly, and of John Wyer’s crucial role, is well told by author Ray Hutton in Ford GT40 – The autobiography of 1075. And if you’d like to see 1075 in action, Jackie Oliver will be reunited with the car at this year’s Goodwood Festival of Speed.

Porsche was so impressed by Wyer’s achievements with a budget much smaller than its own that the company appointed him in 1970 and ’71 to run Gulf-liveried works 917s. These won races but not, frustratingly, Le Mans. Wyer would, however, get to oversee one more Le Mans victory, in 1975: Gulf Research Racing’s Mirage GR8-Ford Cosworth gave Derek Bell his first victory in the 24-hour race and Jacky Ickx his second.

Of all Wyer’s accomplishments, his two wins at Le Mans with an aged blue-and-orange GT40 are surely the most memorable, but he will have been as proud of Porsche’s recognition of his expertise. Wyer was an admirer of Teutonic efficiency, and particularly of Mercedes-Benz’s great pre- and post-war team duo Alfred Neubauer and Rudi Uhlenhaut. Alongside their names, his stands comparison.

Honda, The fastest Lawn mover in the world

The last thing anyone wants to do is spend all day riding around on a slow lawn mower. Or maybe you do—and that’s fine—but for those of us who sweat high-test on a hot summer’s day, Honda is back with another iteration of the Mean Mower. The latest speed record proves this beheader-of-grass is king of the hill—and the holder of a record 6.29-second 0–100-mph run (for a lawn mower).

How fast could a lawn mower mow if a lawn mower was on a race track? It doesn’t roll off the tongue nearly as smoothly or as quickly as the Mean Mower rips through the gears. This latest record entailed stunt driver Jess Hawkins running the “prototype” mower in back-to-back acceleration runs to 100 mph.

The “prototype” designation is likely a bit generous here, as the Mean Mower utilizes the cowling from the production HF2622 mower and… not much else. The powerplant is sourced from the Honda powersports lineup, plucked right from the aluminum frame of the CBR1000RR Fireblade SP motorcycle. It has 200 hp on tap and a totally custom chassis that’s up to the task.

The 6.29-second 0–100-mph sprint is averaged between two runs in opposing directions, and fully certified by Guinness World Records. This isn't the first time Honda has set a record with the Mean Mower, either. In 2014, it set the top speed record at 116 mph. Though unofficial, Honda claims the latest record attempt also showcased the Mean Mower achieving 150 mph on the track’s front straight.

Honda doesn’t mention if the mower deck is still functional, even at slower speeds, but we can dream, right?

Final C7 Corvette sells for $2.7M, and it hasn’t even been built yet

The last C7 Corvette just sold for 33 times its MSRP, and Chevrolet hasn’t even built it yet. The final seventh-gen 'Vette, a black 2019 Z06 coupe with manual gearbox, went for $2.7M at Barrett-Jackson’s Northeast Auction to benefit the Tunnel to Towers Foundation.

Track Day 2019

Track day is September 8, 2019. Don't forget this wonderful event, and, if you never attended before be sure to register for this year. Check your inbox for our previous emails or contact Sports Car Centre by email or phone. Closing date August 31, 2019.

Contact Us

|

Hours

|

||||||||||

Authorized Dealer

![]()

![]()

Sports Car Centre also designs and manufactures custom and enhanced parts for some vehicles.

&width=1300)